The Cost to the City

New York City’s transportation system contains 468 subway stations, 26 subway lines, 6,241 subway cars, 6,300 miles of streets and highways and 12,000 miles of sidewalk. Residents and tourists rely on these systems — along with the rest of the city’s important amenities including sewage systems, beaches and buildings, so when the city floods, it costs — and not just to the infrastructures.

When floods happen, many agencies tout damage estimates, but they are never exact and rarely close to the actual costs incurred because of direct and indirect infringements caused by the flooding.

State, federal and city governments are split into departments and all of them allocate funds when necessary, the press secretary for the NYC Department of Emergency Management Chris Gilbride said. Because of the multiple levels of bureaucracy, he said it is nearly impossible to figure out exact calculations as to how much a flood has cost, even after the water has long dried.

“It’s a long, lengthy process for accounting for eligible cost,” he said. “It comes back as we spend the money so we don’t really count it when it’s applied by agency. Cost estimates are at least initially expert speculation. In June, we’ll have a figure for Irene, but again, it will be a rough figure.”

There is the cost of the actual damage done, but also profit losses taken by closed subway stations, buses, bridges and toll roads, the overtime wages of emergency responders and the costs of emergency supplies.

Irene is said to have cost $27 million to MTA alone. As a result of this damage, Metro-North is providing its customers temporary busing service until repairs are finished at the end of November.

Hurricane Katrina’s estimated cost by Market Watch in September of 2005 was over $100 billion, a price that the journalist received from a private risk assessment firm. In December of 2005, the National Hurricane Center claimed that their cost estimate for the damage it did in New Orleans was closer to $81 billion. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association said that the storm could end up costing the southern coastal states over $125 billion and the country is still paying.

According to Gilbride, $24.5 million is what it takes in New York State to get national emergency declared to to receive money from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). As the money comes back, the city will allocate it to reimburse money it has already spent.

Although Irene's cost won't be official until June 2012, estimates have already been predicted at around one billion in New York State.

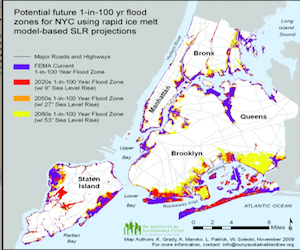

Gilbride does say that being in the geographic location that New York City is in, on an island, makes the city particularly vulnerable to disaster.

“If it rains more than one and a half inches in an hour, we’re prone to urban flooding,” he said.

Former senior scientist at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and Columbia Professor Klaus Jacob wrote about the effects of climate change on New York State. His research found that heavy downpours and coastal flooding have increased and are projected to happen even more frequently, possibly leading to flooding and impacts on water quality, infrastructure and agriculture.

As far as the financial impact of these changes, Professor Jacob’s ClimAID paper states that, “the coastal zone, because of its relative exposure and vulnerability to storms and the concentration of residences, businesses, and infrastructure on the shore, will experience the greatest economic impact of any single region.” Because New York City is on an island, it contains a lot of coastal areas and a higher risk for damage.

Cost to Residents

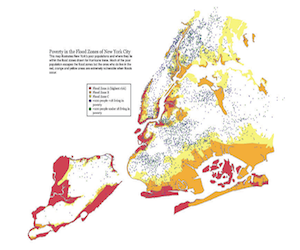

The article also mentioned that the urbanized areas of the state with high population density will have higher public health costs. In other words, New York City is one of the most economically costly places in the state when it floods. There has also been research about how lower-income families with limited mobility are particularly at risk in terms of safety.

“You begin with an environmental justice problem,” said Dr. David Abramson, Deputy Director and Director of Research at the National Center for Disaster Preparedness. “Lower income communities find themselves in more vulnerable areas, lower lying flood plains, where septic systems are less good at preventing flooding. Also the housing that they live in tends to be of lower quality.”

For as much as flooding could cost the city, Abramson also said that

FEMA grants were difficult for these low-income populations to receive, and even if they did get money, spending it properly would be a challenge because they would have no place to go while building repairs were being made.

FEMA grants were difficult for these low-income populations to receive, and even if they did get money, spending it properly would be a challenge because they would have no place to go while building repairs were being made.

Just to evacuate during a flood or hurricane costs around $300 to $500, said Abramson.

“You might say, ‘that’s not too bad,’” he said, “but it is if your total household income is $10,000 a year.”

There have also been studies done to suggest that there is a correlation between lower income and highly localized social networks--so when a disaster hits, poorer populations are less likely to know someone away from their neighborhood who can offer shelter during an evacuation.

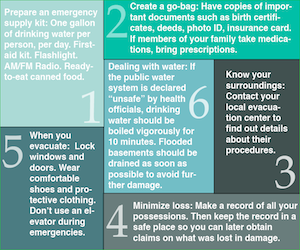

The city’s Office of Emergency Management has been making efforts to communicate with vulnerable populations by translating their "plan ahead" pamphlets into different languages, preemptively building affordable post-disaster shelters and holding community meetings to discuss how to prepare for a hurricane or flood.